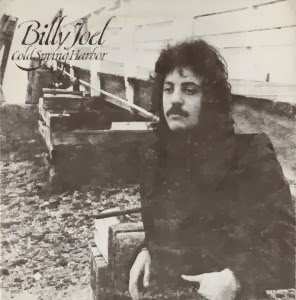

BILLY JOEL: COLD SPRING HARBOR (1971)

1) She's Got A Way; 2) You Can

Make Me Free; 3) Everybody Loves You Now; 4) Why Judy Why; 5) Falling Of The Rain;

6) Turn Around; 7) You Look So Good To Me; 8) Tomorrow Is Today; 9) Nocturne;

10) Got To Begin Again.

One would be hard pressed to think of a more

confused and silly-running beginning of a professional career than Billy

Joel's. So you have just formed one of the strangest combos in rock music and

released one of the most maligned and ridiculed albums of all time, and you

really have no one to blame for that but yourself. So what is your next move?

Naturally, to elope with the wife of your drummer (Elizabeth Small / Joel, whom

Billy would marry in 1972 and divorce ten years later when she got too old for

him, a process that he subseuqently put in replay mode). When this, too, somehow

failed to bring him artistic success, Billy started feeling like a brokedown

table — and drank a whole bottle of furniture polish to remedy the situation.

Had he succeeded in that, B. J. would have forever remained in our hearts and souls as

the «Meat Locker Hun», a perennial scarecrow to shoo novices away from

dangerous musical excesses and distorted organ overdosing. Fortunately, the

good fairy intervened at the last moment and turned the furniture polish into a

20th century equivalent of Brangäne's Love Potion: overnight, Billy woke up

with a sick stomach and the tender, sentimental spirit of a romantic balladeer.

No more ridiculous «hard rock» for yesterday's Hun — in July 1971 he was back

in the studio, recording his first «proper» album for the soft-rock / folk-pop

market.

Cold

Spring Harbor is kind of a

special record in the hearts of some of the fans. Although it is not really

«transitional», since it pretty much lays down all the foundations of the Billy

Joel formula for centuries to come, it still has its own distinct personality

— the relative sparseness of arrangements, where, all too often, it is just

Billy and his piano, sets it apart from the full-band style of Piano Man and subsequent releases, so

we have sort of an Intimate Portrait of the Budding Artist here. Or maybe it's

just the fact that he still got his moustache, I'm not really sure. In any

case, there are backing musicians (such

as Richard Bennett, Neil Diamond's resident accompanyist, on guitar; Emory

Gordy Jr. on bass, etc.), but they are really only there to save the record

from becoming too monotonous.

Of which there is a serious danger, since

Billy's commitment to modern-day troubadour aesthetics is fairly

unidirectional. Completely jettisoning his «psychedelic rock» persona, he now

declares an open love for sweet piano pop in all of its forms — hearkening back

to pre-war vaudeville and Hoagy Carmichael as much as being influenced by Carole

King, Paul McCartney, and that whole newly nascent merger of pop, folk, country,

and watered-down rock which, by 1971, had already became one of the most

popular types of music in mainstream entertainment. Furthermore, Billy selects

the «starry-eyed», «heart-on-sleeve» attitude rather than the self-consciously

ironic or hyper-intellectualized approaches — nothing that would particularly

appeal to fans of, say, Randy Newman or Joni Mitchell.

Under these conditions, the only thing that can

save one's music is raw talent — playing, singing, composing, or, better still,

any of these combined. The problem is that, on all these scales, Cold Spring Harbor registers as «okay».

In the playing department, Billy's self-taught technique is impressive (he

certainly spent far more time practicing than McCartney), but not enough to put

him over any particular top — the instrumental ʽNocturneʼ, for instance, is not

likely to make Chopin roll over, making its point with persistent repetition of

the theme rather than throwing in any intricate variations. As a singer, he

certainly earns more respect here than with Attila, and his tones and phrasing suit his melodies fairly

adequately (it would have been much worse if he'd tried to pull off a Neil

Diamond), but the voice lacks «that certain something» to carve out its own

niche — as much as I like to poke fun at something like Neil Young's whiny

soundwaves, they at least have their own personality, whereas the presence of

any sort of «personality» in the ballads of Cold Spring Harbor (or any of its follow-ups, for that matter) is

under doubt.

What remains are the melodies themselves:

Billy's chief claim to fame — yet they, too, give the impression of

«competence» rather than «genius». A song like ʽShe's Got A Wayʼ has all the external

signs of a gorgeous love ballad, but falls quite a few slices short of a loaf,

earning the listener's love with atmosphere rather than chord sequences or

elegant, admirably symmetric construction of the vocal melody. You'd think

there'd have to at least be some sort of an explosion in the bridge / refrain,

but there is none, other than a slight pitch rise on the final "...I get

turned around", which is basically just a simple cop-out of an unsolved

problem, so it seems. The result is a «pretty», not too annoying, tune that

never truly reaches for those strings that lead directly to the seat of

emotions — and I'd probably rather take something as simple as Paul McCartney's

ʽWarm And Beautifulʼ (a little-remembered tune from Wings At The Speed Of Sound) over this, as well as just about any

other ballad on the album.

As it happens, Cold Spring Harbor wouldn't even begin making it into my personal

Top 100 chart for 1971 (to be fair, nor did it with the general public at the

time, although Billy himself used to ascribe this to an unfortunate incident in

which the tapes were slightly sped up during the vinyl transfer, making him sound

like a bit of a chipmunk — since the reissue, this has been corrected, but who

really knows? maybe the record was

more fun that way). In fact, it is a record that almost invites you to despise

it: mediocre, generic, striving for lofty heights with trivial means, and I

have not even begun to talk about the lyrics. (ʽTomorrow Is Todayʼ is said to

be Billy's recollection of the furniture polish incident — "Made my bed,

I'm gonna lie in it / If you don't come, I'm sure gonna die in it" is

quite a furniture-polish-level couple of lines, to be sure).

Still, somehow, somewhere, just like Attila ended up surprisingly better

than its reputation, Cold Spring Harbor

also exudes a certain mystical charm that prevents me from cringing all the way

through. Maybe it's a matter of production — all this minimalist flair, with

minimal orchestration (Artie Ripp, the guy responsible for the speeding-up

mistake, originally added orchestration to ʽTomorrow Is Todayʼ, but Billy later

removed it). Maybe it's because some of the simple little vocal hooks — very simple little hooks — that Billy

adds to sapfests like ʽYou Can Make Me Freeʼ or ʽTurn Aroundʼ are delivered in

an accordingly simple manner: no pomp means no hate. But most of all, maybe it

is because Cold Spring Harbor is

very much a «homebrewn» affair: unlike, say, a Neil Diamond album or a

Carpenters album, you do not get the feeling of The Big Corporate Machine

backing up Billy's moustache. It's his own game here, sincerely conceived and

honestly laid down. «Poor man's Paul McCartney / poor man's Elton John», for

sure, but at this stage, this is at least an honestly poor man trying to lay

down his feelings as best he can (and doing tolerably well), not a spoiled ugly

millionaire divorcing his third wife.

Check "Cold Spring Harbor" (CD) on Amazon

If you bother, you can check the "incorrect speed version" here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZE3FG7S8Boo. Not exactly Alvin and the Chipmunks but close.

ReplyDeleteI just heard that chipmunk version for the first time. He almost sounds like an immature Demis Roussos. Which probably speaks volumes to its lack of chart action.

Delete

ReplyDeleteDuring my sophomore year in college (’76-’77), I was saturated with Billy Joel’s first three Columbia albums, thanks to my native New Yorker roommate. So, when someone turned up about a year later with a copy of this, I was mind-boggled.

First, the lyrics. They are SO naïve! My roommate called them “uninspired”, which I suppose is true. Only on “Tomorrow is Today” does he approach what he would become in an amazingly short time. And Billy was really no more naïve at this stage than the Beatles were when they came up “Please, Please Me”. Nonetheless, they do have a certain charm, in a sweet, adolescent sort of way. One has to be in the mood for that sort of thing, I suppose.

Then there are the vocals. I didn’t really notice they were off when I heard the original album. But if you listen to the songs side by side with the remix, oh wow! Billy doesn’t sound like a chipmunk, he sounds like Mike Love on too much caffeine. Which is not a good thing. So, correcting the vocals was indeed warranted.

But, for some reason, Artie Ripp(off) was not content with that. He still had control of the master tapes, not Joel. He messed with the original mix in ways that were totally unnecessary.

For instance, he overdubbed strings on “She’s Got a Way” where there were none originally. That doesn’t really affect the song, but doesn’t enhance it, either. On the other hand, he totally stripped out the orchestration on “Tomorrow is Today”. Granted, it was a bit bombastic, but did add some power to the song. It seems more whiny in the new mix. On “Falling in the Rain”, Ripp emphasized the strings more in some places, partially obscuring Joel’s brilliant harpsichord work. “You Can Make Me Free” is chopped in half for no good reason – it’s not like this was an epic double album. Finally, “Everybody Loves You Now” sounds the worst, with the acoustic guitars (still present in the “Songs in the Attic” version) and clunky new drums put in.

This wouldn’t be particularly annoying for the vast majority of fans who has never heard the original. Nonetheless, Ripp could have left well enough alone. Still, the songs are still nice. It’s one of only a few Joel albums I enjoy listening to from beginning to end.