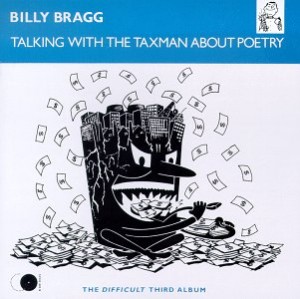

BILLY BRAGG: TALKING WITH THE TAXMAN ABOUT POETRY (1986)

1) Greetings To The New

Brunette; 2) Train Train; 3) The Marriage; 4) Ideology; 5) Levi Stubbs' Tears;

6) Honey, I'm A Big Boy Now; 7) There Is Power In A Union; 8) Help Save The

Youth Of America; 9) Wishing The Days Away; 10) The Passion; 11) The Warmest

Room; 12) The Home Front.

Finally, after years of hardcore studio busking, Billy

Bragg relents upon us — if only a little bit. There is still a lot of

minimalistic electro-busking here, but on many of the tunes, Billy agrees to

use additional musicians, sometimes even including a rhythm session, with John

Porter playing bass and several different percussionists, one of which happened

to be Kenney Jones himself (ex-Small Faces and ex-Who), who also took upon

himself the production duties. Ken Craddock on organ, Dave Woodhead on trumpet,

and even Johnny Marr on guitar also make appearances, continuing their

relations with Billy from where they left off on the previous album.

Concerning the album title, I was all set to

make some clumsy joke around it when I fortunately discovered that it was

actually the translation of the title of a Russian poem by Vladimir Mayakovsky

(something I would never have guessed on my own because the Russian original

has the convoluted financial inspector

rather than taxman — the poem was

published in 1926, when the USSR had no «taxmen» to speak of) — the main idea

of the poem being «defense of poet's honor», stating that the profession of a

poet is a legitimate occupation even in the new world, ruled with the iron fist

of the proletariat dictature. Honestly, I am not quite sure how that point is

to be applied to this Billy record — other than implying that he is somehow

justifying himself for not working in the coal mines, back to back with The

People, but rather sitting his ass off in a warm recording studio, because,

well, if The People want their champion, they have no choice but to let him sit

his ass off in Livingston Studios, London. I mean, he probably could take his

guitar and his tape recorder and record these songs right in the coal mine, but

then they'd sound... dusty. No chance of getting any hit singles that way.

In any case, the album seems better constructed

than Brewing Up: lyrically and

musically, there are more nuances here, and the record does not immediately

come off as this unnatural, clumsily constructed «now I'm singing about

people's rights» — «and now I'm singing about bitches» — «and now I'm singing

about people's rights again» — «and now I'm singing about bitches again»

monstrosity. Mind you, he is still

mostly singing about people's rights and bitches, but the song titles, the

melodies, the lyrical imagery become more diversified, and in fact, you know

what? in the very first song, he actually combines

the two aspects: "Shirley, your sexual politics left me all in a muddle /

Shirley, we are joined in the ideological cuddle... Politics and pregnancy /

Are debated as we empty our glasses...".

Unfortunately, even though there are more

pianos, trumpets, and bass guitars on the album as before, I also have to

state that this comes at the expense of interesting melodies. The most obvious

case is ʽIdeologiesʼ — which is simply a cover of Dylan's ʽChimes Of Freedomʼ

with new, «updated» lyrics by Billy, and even if he is not stealing it, but

honestly indicating Dylan as a co-author in the credits, this is somewhat

symbolic: lyrics and pure passion have completely overridden his pop writer

instincts. This is not a crime — in fact, it may be a deliberate and rational

decision, because the man would hate to be labeled as a «pop artist» anyway —

but it still makes me sad. Intelligent political statements set to pop hooks

give you so much more than just

intelligent political statements (even if intelligent political statements by

pop artists are by themselves much preferable to any political statements by

politicians).

The most musically interesting songs here are

the subtlest and most psychological ones: ʽThe Marriageʼ, a seemingly weak

protest against the ties of society ("marriage is when we admit our

parents were right", the chorus goes), is set to an interesting mish-mash

of choppy jazz chords, blues lines, and flamboyant trumpets that has no direct

analogy in the past — and ʽThe Passionʼ, symmetrically disposed on the second

side of the album, also has a wonderful gliding waltz melody, not as original,

but with a very deep and tender-sounding weave of two guitars sliding in and

out of each other, as if symbolizing the now agreeing, now discordant relations

between kids and parents that forms one of the lyrical topics of the song. There's

also ʽLevi Stubbs' Tearsʼ, a mildly haunting portrait of an outcast whose only

source of permanent comfort are The Four Tops (and suchlike) — a good example

of the man's busking technique where he alternates between throttling/choking

his guitar and letting it wail free: again, not particularly original, but very

well suited for the character he is singing about.

Political stuff like ʽPower In The Unionʼ and

ʽHelp Save The Youth Of Americaʼ (I do hope there was some sort of a plan to

spread the song in the States — I mean, who really needed it in the UK?) is of

passable interest because of the lyrics and little else. The Randy Newman-esque

ʽHoney, I'm A Big Boy Nowʼ, with its shambly tack piano and nonchalant country

attitude, also shows that this kind of music should better be left to musicians

across the other side of the ocean; and ditto for ʽWishing The Days Awayʼ,

which may be a parody on the Nashville style for all I know, but it hardly

works even as a parody — more like a pack of people that decided, for no reason

at all, to record a country song despite having had no experience whatsoever.

Or maybe they're intentionally «deconstructing» it, I don't think it works

anyway. On the other hand, ʽThe Warmest Roomʼ is an almost accomplished pop song — all it needs is a nice, memorable

lead line, and this would be as close as the album comes to a potential hit

(not that there was ever any thought about releasing it as a single: that honor

fell to the somber ʽLevi Stubbs' Tearsʼ).

It would be almost impossible to say that the

focal point of the albums are not its lyrics — for Billy, the meaning of what

is sung is clearly more important than the manner in which it is sung (which is

why serious comparisons with Dylan would be out of question), and it is good to

know that, once again, his idea of «championing the people» is not so much to

throw shit at The System as it is to try and pull the people themselves out of

their somnambulant state, which is why we have all these character portraits of

disenchanted lovers, disillusioned housewives, Mother and Father and Grandma,

presented with just as much psychologism (sometimes more — after all, we're

standing on the shoulders of giants and all that) as in any poem by Ray Davies

or (early) Tom Waits. Still, now that the original novel shock at the sight of

«electro-busking» has passed, Taxman

comes across as a somewhat hesitant, and not very interesting transitional

record: even all these extra musicians still do not feel like they have been

properly integrated with Bragg's original solitary vision. A few nice songs,

but nothing spectacular.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.