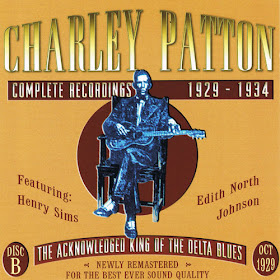

CHARLEY PATTON: COMPLETE RECORDINGS: VOL. 2 (1929/2002)

1) Hammer Blues (take 1); 2) I

Shall Not Be Moved; 3) High Water Everywhere, Pt. 1; 4) High Water Everywhere,

Pt. 2; 5) I Shall Not Be Moved; 6) Rattle Snake Blues; 7) Going To Move To

Alabama; 8) Hammer Blues (take 2); 9) Joe Kirby; 10) Frankie And Albert; 11)

Magnolia Blues; 12) Devil Sent The Rain Blues; 13) Runnin' Wild Blues; 14) Some

Happy Day; 15) Some Happy Day; 16) Mean Black Moan; 17) Green River Blues; 18)

That's My Man; 19) Honey Dripper Blues No. 2; 20) Eight Hour Woman; 21)

Nickel's Worth Of Liver Blues No. 2.

Patton's second recording session dates back to

October 1929 and was so huge that it had to be spread over two CDs — granted,

unlike the June session, this one is not officially tied to particular dates

and could have been stretched over several days of recording. It was also

recorded in a different place — Grafton, Wisconsin, which might explain the

notoriously evil difference in sound

quality: most of the tracks are so choked with crackle and hiss that it is

downright impossible to listen to them for anything other than pure curiosity.

Still, this is where you will find one of the

man's most classic numbers, the two-part ʻHigh Water Everywhereʼ, commemorating

the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, but also, in some mystical way, sounding

like a grim harbinger of the troubles to come (as the first wave of the

Depression would hit the country at the very end of the same month in which the

sessions were held). The two parts are just a technicality that allows the

6-minute epic to be spread across two sides, and much of that 6-minute period

is spent beating the crap out of the man's guitar (literally), as Mr. Patton gives us his most primal-tribal sound and

atittude so far — the percussive aspect is not about dancing, it is all about

communication with the spirits, in the general direction of whom the man is

registering his formal complaint. I wouldn't call this sort of thing haunting

or mesmerizing for the modern listener's ear, of course, but it does not take

much of an effort to try and carry yourself back to the time when it was — just play the whole thing back to

back with some Bing Crosby from the same year, and it'll be all right.

On six of these tracks, Patton is accompanied

by Henry Sims on fiddle, predictably lending the sessions a bit of a country

air — particularly effective on ʻGoing To Move To Alabamaʼ, a swaggery

country-dance tune that would be perfect for Jimmy Rogers or even Hank

Williams, except here it's being sung by Mr. Black Devil In The Flesh himself.

Actually, listening to this track and then

listening to some of the bluesier tunes by Mr. Rogers from the same years makes

it glaringly obvious how flimsy and arbitrary the borders between «blues» and

«country» were at the time, and how ridiculously more pronounced they would

become over time. It's a doggone shame that most of the tracks are in such

awful quality — Sims plays some fairly sensitive and technically tricky

passages on ʻMean Black Moanʼ, but you will have to get yourself a couple of

dog ears to truly appreciate them.

A special highlight is Charley's rendition of the

gospel hymn ʻI Shall Not Be Movedʼ, available here in two different takes, only

the second of which is properly listenable — what's fun about it, though, is that the

first take is consistently slow and stately, whereas the second one starts

exactly the same way and then, one minute into the song, suddenly speeds up

almost to the same merry tempo with which it would later be performed by Johnny

Cash. Both approaches, the more introspective and prayer-like slow one and the

more energetic and passionate fast one, have their merits, but it is the

«experimental» transition that is the main point of interest.

Just as it was on the first disc, the last

several tracks have little, if anything, to do with Patton: four piano-led

urban blues tunes with a lady called Edith North Johnson on vocals. She's okay,

but she ain't no Bessie Smith or Alberta Hunter (in fact, it seems that she

really gained access to the studio only through her marriage to the St. Louis

record producer Jesse Johnson), and the only reason for the inclusion of these

tracks is an almost-disproved rumor that Patton may have played guitar on the first of these, and to be perfectly

honest, I don't even hear any guitar

on it. Maybe he was just strumming something outside the studio while the

recording was on... anyway, no harm in choosing this manner of preservation of

a perfectly harmless batch of generic second-rate urban blues tunes riding the

coattails of a major legend, right? That's one generous way of helping the name

of Edith North Johnson, at least for a brief while and for a small audience, to

escape the clutches of total oblivion. Besides, something like ʻNickel's Worth

Of Liver Bluesʼ is well worth salvaging for the awesome title alone.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete(lets try again). and this is it, the location of the studio. This is about as exciting as thing get in Grafton

Deletehttps://www.google.com/maps/@43.3095106,-87.9519163,3a,75y,59.38h,76.87t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1slLw_QSEmIB7vTdbUvnCsKQ!2e0!7i13312!8i6656?hl=en-US