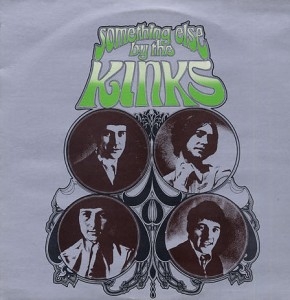

THE KINKS: SOMETHING ELSE BY THE KINKS (1967)

1) David

Watts; 2) Death Of A Clown; 3) Two Sisters; 4) No Return; 5) Harry

Rag; 6) Tin Soldier Man; 7) Situation

Vacant; 8) Love Me Till The Sun Shines; 9) Lazy Old Sun;

10) Afternoon Tea; 11) Funny Face; 12) End Of The

Season; 13) Waterloo Sunset; 14*) Act

Nice And Gentle; 15*) Autumn Almanac; 16*)

Susannah's Still Alive; 17*) Wonderboy; 18*)

Polly; 19*) Lincoln County; 20*) There's No Life Without Love; 21*) Lazy Old

Sun (alternate take).

On a purely formal basis, the leap from Face To Face to Something Else is neither as huge or as unpredictable as the leap

from Kink Kontroversy to Face To Face — this is, essentially,

just Vol. 2 of Ray Davies' ongoing project on the «Personal History,

Adventures, Experience and Observation of Select Members of the British Society

(Which They Never Meant to Publish on Any Account, But Took Kind Advantage of

Mr. Ray Davies to Do for Them)». Some of the more critical contemporary reviews

actually latched on to that, complaining that Ray's passion had become an

obsession, and that the Kinks were becoming boring and formulaic, instead of pushing

forward and breaking the good old boundaries.

So why is it that, eventually, Something Else emerged as a critical

darling, typically rated maybe half a notch below Village Green as the ultimate Kinks experience? The inclusion of

ʽWaterloo Sunsetʼ, Ray's equivalent of ʽYesterdayʼ in the public conscious, has

a lot do with it — but mostly, I guess, it is the tacit understanding that Something Else was the first Kinks

album on which Ray's artistic vision is given to us without any signs of

compromising. In 1966, he was still a pop songwriter, albeit a brilliant one —

yet for each ʽSunny Afternoonʼ, there was still an ʽI'll Remember Youʼ, nice

formulaic pop songs without a soul of their own. If Face To Face was their Rubber

Soul, a brilliant record with certain elements that still tied the band to

their somewhat more constricted past (like ʽWaitʼ, etc.), then Something Else is their Revolver: a record where each and every

song transcends mere «good» and heads straight for the upper levels of

«revelatory» or, at least, «insightful».

In terms of stunning musical breakthroughs, it

is hard to say in which precise spots Something

Else hits anything like that. Apart from a little bossanova on ʽNo Returnʼ

and maybe a bit of French pop influence on ʽEnd Of The Seasonʼ, Ray here is

perfectly fine sticking to the same old sources of inspiration: a little pop, a

little music hall and vaudeville, a shot of rhythm'n'blues to make sure the

wolves still have their teeth intact, and a splash of the harpsichord to show

that they are still committed to that baroque-pop spirit. From this point of

view, the album is not really «something else!» with an exclamation sign, more

like a humble, excusatory «just something else» without demanding any

unreasonably high expectations. The real task that Ray sets for himself has

little to do with «blowing minds» by means of strange sounds never heard before,

and everything to do with writing a perceptive chronicle of everyday life in

his native country — life as it happens to people who might never have even

heard of the UFO Club — and presenting it in the format of catchy, easily accessible,

and aurally friendly pop tunes.

So far, so good. But here is the true catch

that separates Something Else (and

its follow-ups) from oh so many pop-rock and roots-rock albums championing the

underdog: believe it or not, it actually has a very distinct psychedelic flavor

of its own, though it has nothing to do with the psychedelia of Sgt. Pepper, Piper, or Are You

Experienced?. Because first and foremost, Ray Davies is not actually a

chronicler: Ray Davies is a dreamer.

Most of his best songs are dream tunes — fantasies that are grounded in

reality, but twist it according to their creator's impulses,

"I-wish-it-were-so" types of songs. "Wish I could be like David

Watts", "living in a little tin wonderland", "as long as I

gaze on Waterloo sunset, I am in paradise", these are just the most

obvious bits on this particular album. With the exception of just a few obvious

downers such as ʽDead End Streetʼ, Ray seems to have sworn off thoroughly

depressing songs forever — no matter how gloomy the reality, it is always

within your mindpower to create a bubble of light in which you can safely

deposit your conscience. This is the essence of Ray's unique vision, and Something Else is the first of several

records on which it turns out to be fully realized.

What I mean is that ʽDavid Wattsʼ is a fun song

whose continuous fa-fa-fa-fa's will

probably stick in your head with the same ease as the Beatles' yeah yeah yeah's; but it is also more

than a fun song — it is a song about "lying on your pillow at night",

with echoes of today's vivacious school team performance still in your head,

and fantasizing about what it would take to live somebody else's life. (Given

that the real life David Watts, according to Ray's memoirs, was gay, some

people offer a homoerotic interpretation to the song, but sexual themes are

clearly not its main point — the protagonist does not wish to fuck David Watts,

he wishes to be David Watts). Just

think of the song's crude, monotonous, crazyass-pulsating bass/piano duet as a

musical representation of one's wildly pulsating brain, still heavily

adrenaline-charged from the day's events, and all of a sudden, ʽDavid Wattsʼ is

no longer just a funny-silly novelty tune, but a masterful exercise in music

psychology.

Fast forward a bit to ʽTin Soldier Manʼ, and

the pattern repeats itself, except that this dream is not so much a wish

fantasy as an impressionistic metaphor — portraying your routinely disciplined,

punctual, petty-tyrannical neighbor as a living and breathing tin soldier, to

the sounds of one of the catchiest and

most carnivalesque military marches ever written in the land of Gilbert and Sullivan.

It is not a mean song, though: you

may read your social criticism into it if you wish, but you may just as well

look at it as a grown-up child's instinctive impression of the behavioral

patterns of his curious neighbor. There is certainly nothing bitter or sardonic

in the music, those bouncy,

uplifting, toy-military chords that get your feet tapping (it is probably one

of my own most-often-whistled melodies of all time, because how can you ever

abstain?..): Ray is building up his own little collection of Pictures At An Exhibition, open for your

own additional interpretation: take pity on the tin soldier man, despise the

tin soldier man, or simply take the time to tap your foot and admire him as an

exotic exhibit.

Fast forward once again, to the very end, and

the reason why everybody loves ʽWaterloo Sunsetʼ is because the whole song is a

dream — or, at least, a piece of alternate reality that the hero has

constructed for himself, completely blocking out those "millions of people

swarming like flies 'round Waterloo underground" and fully concentrating

on Terry and Julie instead (and still preferring to admire them from afar

rather than introducing himself directly into their lives). The usual focus of

attention here is brother Dave's dense and juicy guitar tone, coming in colours

everywhere from your speakers; but for me, the chief hook of the song comes with

Ray's rising to dreamy falsetto on the "but I don't... need no

friends" and "but I don't...

feel afraid" mini-bridge: this is the part where quiet, peaceful

observation is brilliantly resolved into some sort of internalized spiritual

orgasm — the protagonist being at peace with the world as long as the world

does not bother him and lets him freely concentrate on select individual spots

of beauty that he has chosen for himself. In a truly alternate reality where

literature characters come to life and move freely across time, this would

probably have been Boo Radley's favorite song.

Of course, Something

Else also features plenty of songs where the outside observer seems to disappear,

giving way to third-person narratives about peculiar types of situations: ʽTwo

Sistersʼ, for instance, about a quiet and ambiguous rivalry between a housewife

and a socialite, or ʽSituation Vacantʼ, about how your mother-in-law can

really spoil your day (indeed!). But even ʽTwo Sistersʼ sounds dreamy, with

Nicky Hopkins' harpsichord melody taking your mind far away from the possible

reality of the song — let alone the fact that the story of two sisters only

serves as an allegory for two brothers (Ray and Dave), which is certainly not a

fact that one is obliged to learn in order to enjoy the tune as a modern fairy

tale (and, for that matter, don't the names Sylvilla and Percilla actually sound

as if taken from something by Charles Perrault?). ʽSituation Vacantʼ is a

harsher, harder-rocking little number with distinct bluesy overtones (still,

even that does not prevent Hopkins from inserting a few extra baroque piano flourishes),

but, hilariously, it is also the one song on the album that comes closest of

them all to traditional psychedelia — you just have to watch for the coda and

its combo of ghostly falsettos, buzzing lead guitars, and wobbly bass piano

chords. It does not fit in all that well with the overall mood of the album,

but a bit of unpredictable diversity never hurt a great record.

And what about brother Dave? He has a hard time

living up to Ray's level, but at least he has the good sense to cautiously follow

in his footsteps than insist on recording ferocious rock'n'roll and spoiling

the party for good. ʽDeath Of A Clownʼ, the song that almost won him a solo

career, fits in brilliantly with Ray's subject matter — not as dreamy and

reclusive, given Dave's extroverted nature, but providing the picture gallery

with another subtly painted character portrait (for some reason, «sad clown» imagery

was really popular with British pop

bands around 1966-67: the Hollies, for instance, had at least a couple of songs

devoted to the same matter). ʽLove Me Till The Sun Shinesʼ and ʽFunny Faceʼ are

nowhere near as catchy and sound inspired by Small Faces, but Dave is no Steve

Marriott when it comes to belting, and the Kinks' rhythm section cannot hope to

match that competition in terms of power and crunch, but at least both songs

are still in a pop vein and do not detract from the overall mood. ʽFunny Faceʼ

does stick out as a bit of a sore thumb in between the stylishly sentimental

ʽAfternoon Teaʼ and ʽEnd Of The Seasonʼ, which is probably why my brain always

tends to scratch it out of existence.

So much said and I have not even had the chance

to extol the virtues of ʽHarry Ragʼ (ruffiest and gruffiest and funniest and

catchiest ode to tobacco ever recorded!), or those of ʽLazy Old Sunʼ (another

brave attempt at hammock-style psychedelia), or the decidedly uncatchy, but

charming bossanova experiment of ʽNo Returnʼ — and then there are the bonus

tracks on the CD edition, representing contemporary A- and B-sides, all of

which are treasurable one way or the other, and most of which would

legitimately fit in the same picture gallery. Of these, it is impossible not to

say a few words about ʽAutumn Almanacʼ, a solid contender for the most accomplished

and, well, fundamental song Ray ever

wrote — not only is it technically brilliant, combining a catchy chorus with a

never-ending stream of fluctuating-alternating verse melodies that flow in and

out of each other more smoothly than rivulets, but it's got Ray's entire

emotional palette (tenderness, humor, sympathy, humility, sadness, nostalgia —

everything but anger and bitterness, which he was moving away from at the time)

flashing across your brain in three minutes time: submit to it properly and it might

just leave you a better person by the end, or at least make you think more

fondly of the autumnal season. There's more ideas and feelings contained in

that one pop song than in an entire pop album by the average pop artist — Ray

sure as hell ain't greedy with his hooks, and the result is a masterpiece that

always sounds fresh and exciting, no matter how many times I hear it.

"This is my street and I'm never gonna leave it", in particular,

despite the soft and feeble delivery, is as decisive and definitive a statement

as any punk slogan ever voiced.

That ʽAutumn Almanacʼ became the last Kinks

single until ʽLolaʼ to hip the Top 10, and that Something Else became their last album ever to chart at all in their native homeland is at the same time

understandable and bewildering —

understandable because people like loud, flashy, egotistical thingies that help

them tickle their pride or rally their resources, but bewildering because while

he was still in his prime, Ray never

betrayed the cause of the well-crafted pop hook (or a whole smattering of

those) in favor of his lyrical portraits or sentimental mood swings. With the

exception of ʽNo Returnʼ (too jazzy) and ʽFunny Faceʼ (too Davey), I can still

vividly remember how each song here goes without listening to the album for

years — and the same goes for vaudevillian singles like ʽWonderboyʼ, allegedly

well-loved by John Lennon (it does have a bit of the «positive John» mood in

it) but despised by the record-buying public back in early 1968, though,

frankly, it is just not as anthemic as ʽHey Judeʼ, but it also teaches you to

love life and take it as it comes in memorable verses and choruses. Perhaps

they should have attached a four-minute epic coda of la-la-la's at the end?..

Anyway, fortunately, by the 21st century the

reputation of the album — and post-ʽSunny Afternoonʼ Kinks in general — has

recovered so well that there is no sense defending it; there is only sense in

trying to understand and interpret it to the best of one's ability, and explain

why it is one of the most intelligent and

emotional artistic representations of one person's inner world in 1967. There

are psychological corners explored here that you won't find on Sgt. Pepper, or on Smile, or on any other of those albums with their big guns, blasting

away at the sun, while Ray Davies here is just fussing around with his

microscope. And, of course, this does not make Something Else better than any of those albums — it is simply

needed to round out and complete the picture of 1967 as one of the most awesome

years in popular music. "Lazy old sun, what have you done to

summertime?" is the Kinks' perfect response to the Summer of Love; and,

for what it's worth, the album came out on September 15, opening Ray's personal

Autumn of Sympathy, which is every bit as deserving of its own thumbs up.