Today's IAS review is:

Radiohead: Kid A

Be warned, though. Not for the faint-hearted. Abandon hope and all that.

Sunday, January 31, 2016

Saturday, January 30, 2016

Cabaret Voltaire: Red Mecca

CABARET VOLTAIRE: RED MECCA (1981)

1) A Touch Of Evil; 2) Sly

Doubt; 3) Landslide; 4) A Thousand Ways; 5) Red Mask; 6) Split Second; 7) Black

Mask; 8) Spread The Virus; 9) A Touch Of Evil (reprise).

Prior to Red

Mecca, the band had released an EP called Three Mantras — a musical representation of their views on

religious fundamentalism, Christian and Islamic, by means of a ʽWestern Mantraʼ

and an ʽEastern Mantraʼ respectively (the liner notes jokingly apologized for

the lack of the promised third mantra and explained that the record was

underpriced to make up for that). However, even though each of the tracks ran

for twenty minutes, they felt this wasn't nearly enough, and eventually

followed it up with a longer, more «comprehensive» album, aptly called Red Mecca so they could offend

everybody. Frickin' hatemongers.

This is often seen as one of the highest points

in the band's career — probably because it is the first Cabaret Voltaire album

which feels like a self-assured statement, rather than just another incoherent

bunch of some-of-it-works-and-some-of-it-oh-me-oh-my experiments. It also feels

better produced than before, even though they were using the same studio in

Sheffield as always (maybe they got better insulation on the windows or fixed

some of the wiring, I have no idea). Other than that, though, it's just another

Cabaret Voltaire album, meaning that its sounds, at best, are interesting and

curious rather than «grappling».

The record symbolically opens with an

industrial/avantgarde reworking of Henry Mancini's opening theme for Orson

Welles' Touch Of Evil — a movie that

did not deal with religious issues as such, if I remember it correctly, but did

dabble around in various sick corners of the human nature; and it is good to

have that hint, because the band's drab, morose soundscapes aren't exactly

reminiscent of «evil caused by mankind» on their own. If I knew nothing about

the sources of the recording, I would have regarded it... well, I still regard it as essentially the

musical equivalent of taking a slow, uncomfortable, stuffy ride on some creaky underground

train through a long row of caves, tunnels, grottoes, and mines populated by

freaks, mutant dwarves, and methadone-addled incorporeal ghosts of Nazi

criminals.

The «danceability» is faithfully preserved and

even enhanced by a more musical than ever before use of brass instruments, but

this still is no music to dance to: ten and a half minutes of ʽA Thousand

Waysʼ ultimately sound more like an incessant, nerve-numbing «musical

flagellation», with the percussive whips making as much damage to your body as

the incomprehensible vocal exhortations do to your soul, than something to

dance to (and besides, it's pretty hard to dance while being whipped). The bass

groove of ʽSly Doubtʼ is as funky as anything, but when it is coupled with a

synthesizer «lead melody» that resembles airplanes flying over your head, your

sense of rhythm will be confused and shattered anyway. Same thing with the

antithetical pairing of ʽRed Maskʼ and ʽBlack Maskʼ, except that guitars and

keyboards on the former sound like malfunctioning electric drills, and on the

latter like the soundtrack to an arcade space shooter.

Unfortunately, in one respect Red Mecca remains undistinguishable

from any other Cabaret Voltaire release: it is hard to get seriously excited

over any of these tracks, even if they sound cleaner, tighter, and imbued with

sharper symbolical purpose. Memorable musical (or even «quasi-musical») themes

are absent (the shrill, whining riff of ʽLandslideʼ is probably the closest

they get, but even that one is nothing compared to what a Joy Division or a

Cure could do with such an idea), «energy level» is not even a viable

parameter, and there is almost no development — ʽA Thousand Waysʼ, after ten

minutes (years) of that flagellation, leaves us exactly where it found us, and

so do most of the shorter tracks as well.

This is why, in the end, I cannot permit myself

to give out a thumbs up rating here: important as this album could be upon

release, it does not seem to have properly stood the test of time. Even its

symbolism has to be properly decoded with the aid of additional sources, and

even if you do decode it, it is

hardly a guarantee that from then on you'll be wanting to stick the CD under

your pillow every night. It's interesting — but it's also boring. Which is a

very basic characteristics of the band as a whole, of course, but since Red Mecca is often highlighted as «the

place to start» with these guys, be warned: it's not too different from

everything else they've done, and unless you've heard no experimental electronic

music whatsoever post-1981, it's not highly likely to provoke a revelation. For

historical reasons, though, it's worth getting to know.

Friday, January 29, 2016

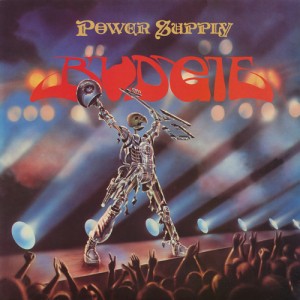

Budgie: Power Supply

BUDGIE: POWER SUPPLY (1980)

1) Forearm Smash; 2)

Hellbender; 3) Heavy Revolution; 4) Gunslinger; 5) Power Supply; 6) Secrets In

My Head; 7) Time To Remember; 8) Crime Against The World.

I used to be excessively harsh on this album,

and, in truth, it is hard not to be

harsh on an album that sounds like an unimaginative cross between Judas Priest

and AC/DC. But then it might also be a little silly to accuse Budgie jumping on

the early Eighties metal bandwagon, if only because Budgie had always been professional wagon-jumpers,

ever since ʽGutsʼ so openly nicked off the Sabbath sound ten years before. So

how could we call it a crime when, upon Bourge's departure from the band,

Shelley instigated a transition into more «modern» territory?

If there's a problem here, it is with Shelley's

personality. One thing that early Eighties metal demanded was brutal, sweaty,

swaggering frontmen that could match the sweat, brutality, and swagger of that

new guitar sound — and Burke Shelley, with his lean lanky nerdy figure, whiny

vocals, and encumbering bass, could hardly qualify. His voice is high-pitched

enough, for sure, and he can raise it to a proper scream when necessary (see

the chorus to ʽHeavy Revolutionʼ), but it has none of the steel overtones of a

Brian Johnson or a Bruce Dickinson, and that scream can never turn to roar;

just not the same level of aggression, sorry. Just like it's hard to imagine

Geddy Lee doing a credible cover of ʽHell's Bellsʼ, or something like that.

New guitarist John Thomas is quite competent,

though, I'll give them that. He can come up with riffs that are almost as good

as K. K. Downing's, and he can play insane-delirious solos just like Angus

Young — both these skills are immediately evident on the opening number,

ʽForearm Smashʼ, where in the mid-section they nearly pull off a ʽWhole Lotta

Rosieʼ. ʽHellbenderʼ and ʽHeavy Revolutionʼ are also not half-bad, riff-wise,

with all those nasty tones and clever use of stock metal licks. Nothing too

special, but the instrumental sections of these songs are seriously enjoyable —

provided you like the not-too-experimental, ass-kick-oriented style of early

Eighties metal in general, I don't see how it is possible not to toe-tap or

play at least a little air guitar to these songs. They're fun.

If you try to subject them to a little closer

analysis... well, don't. You might stumble upon the lyrics to ʽHeavy

Revolutionʼ, which seem to be a sincere

appraisal of the arena-rock image: "Our heads jumping up and down / Heavy

rock bands are back in town", without a single noticeable shred of irony —

quite embarrassing to see them associated with Mr. Shelley and his nerdy looks

(it's a good thing that no video footage of the band from that era has been

preserved). Essentially, all of Budgie's «cleverness», including those nutty

song titles which used to relate them to Blue Öyster Cult, seems to have

evaporated, replaced with far more explicit and provocative imagery. Not that Budgie

lyrics have ever mattered much — and the words do go well with the music, they

just don't go all too well with the singer.

There's exactly one power ballad in the mix

(ʽTime To Rememberʼ), mediocre, but not awful (depending on whether you think

the echo on Shelley's vocals — "time... time... time... to remember"

— is an impressive or a stupid idea). There's exactly one song with an acoustic

introduction (ʽGunslingerʼ) that dutifully segues into an epic rock guitar

battle of life against death. There's exactly one slow rocker (ʽCrime Against The Worldʼ) that concludes the album on

an almost relaxed note compared to most everything else. And most everything

else taps their not-so-large «power supply» to the max. So at least they're

going for it hardcore-style — no «sissy keyboards», not too much overblown

sentimentality. Certainly could be worse, had they hired a less competent

guitarist. But do remember that this is «Budgie 2.0», a completely different

thing from what it used to be, and even if you loved Impeckable, you have to have yourself a ʽHeavy Revolutionʼ to love Power Supply.

Thursday, January 28, 2016

The Byrds: Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde

THE BYRDS: DR. BYRDS & MR. HYDE (1969)

1) This Wheel's On Fire; 2)

Old Blue; 3) Your Gentle Way Of Loving Me; 4) Child Of The Universe; 5)

Nashville West; 6) Drug Store Truck Drivin' Man; 7) King Apathy III; 8) Candy;

9) Bad Night At The Whiskey; 10) Medley: My Back Pages / B. J. Blues / Baby

What You Want Me To Do.

Finally, we move on to the very last chapter of

the transformational history of The Byrds. With Chris Hillman and Gram Parsons

departing to form The Flying Burrito Brothers, the only surviving member is

Roger McGuinn, and his new team includes Gene Parsons (no relation to Gram) on

drums, John Yorke on bass, and Clarence White on guitar (Clarence had

previously sat in with the band on some of the 1968 sessions, and had already

joined the band as a replacement for Gram Parsons in the brief interim when

Hillman still remained an active member). But even though the new musicians are

all quite decent, it took some time before the whole thing clicked, and Dr. Byrds & Mr. Hyde shows a

certain lack of direction.

Actually, my biggest problem with this record

is that there are way too many McGuinn originals, and most of them — nay, all of them — are deeply problematic.

ʽChild Of The Universeʼ? Lots of lyrical pretentiousness, a touch of grand

pathos provided by the booming percussion fills and Spanish guitar lead fills,

but the melodic drone is just too monotonous and the transitions between verse

and chorus too un-dynamic to make you go wow — and let's face it, if a song called

ʽChild Of The Universeʼ does not make you go wow, too bad for the song, not the

universe.

ʽKing Apathy IIIʼ is an even stranger and

clumsier experiment that sews together a fast blues-rock verse with a slow

country-western bridge — the song has a very clear lyrical message, in which McGuinn

renounces the "middle class suburban children" who "blindly

follow recent pipers" and states that "I'm leavin' for the country,

to try and rest my head", and it's his choice and all, but illustrating it

with a poorly joined-at-the-hip mix of generic bluesy psychedelia with generic

country waltz is at best boring symbolism, and at worst an embarrassment in

both genres (let alone all the condescending remarks about "liberal

reactionaries" who are busy "slowing down their B. B. King" —

not quite on the level of Lennon's "fuckin' peasants" yet, but slowly

getting there, although at least Lennon could sound real passionate about the

issue).

Hilariously, McGuinn manages to offend both the progressive liberals and the hillbilly conservatives on the

album: ʽKing Apathy IIIʼ is the immediate follow-up to ʽDrug Store Truck

Drivin' Manʼ, a remainder of the McGuinn/Parsons collaboration that rhymed the

song title with "the head of the Ku Klux Klan", was inspired by a

clash with the obnoxious Nashville DJ Ralph Emery, and must have probably been

a sweet, sweet joy to perform during the band's tour of the Bible Belt (just

joking — actually, they preferred California, but whether they dared perform

ʽKing Apathy IIIʼ there, I have no idea; then again, most of the hippies would

probably be way too stoned to notice the words). Not that it's a particularly

good song, either, but at least it sort of evens the odds for representatives

of both parties. See, Roger McGuinn doesn't really like anyone, so what's the

big surprise about the album selling more poorly than ever before?

In the light of these and other, not much

better, failures at decent songwriting, the best thing about Dr. Byrds are its covers — starting

with the hard rock of ʽThis Wheel's On Fireʼ, for which Clarence recorded a

heavily distorted, brutally angry guitar part that suits the song's lightly apocalyptic

mood very well (the CD reissue adds an alternate take with a much lighter

guitar arrangement if you insist that hard rock and Byrds should never mix,

but I don't think we need be so strictly prejudiced). Contextually, that track

is pretty deceptive — the sequencing contrast between its angry roar and the

following sentimental country tweeting of ʽOld Blueʼ may be the single sharpest

contrast in Byrds history — but I suppose it made some sense, to try and

demolish the perception that from now on, the Byrds are a «country band»,

period. However, most of the other covers are

country, with songs like ʽYour Gentle Way Of Loving Meʼ and the speedy instrumental

ʽNashville Westʼ totally belonging on Sweetheart

and, in fact, being better than most of the stuff on Sweetheart (ʽNashville Westʼ has some pretty pleasing guitar

interplay).

Still, by the time they get to the odd closing

medley that puts Bob Dylan and Jimmy Reed on the same stage (how do ʽMy Back Pagesʼ, a song that the real

Byrds already had recorded, belong together with ʽBaby What Do You Want Me To

Doʼ? Nohow is the answer), by the time they do this, the overall impression of Dr. Byrds is that of a total mess.

There are enough talented people here to guarantee that it works in bits and

pieces, but they don't know where to go. They know where they don't want to go, all right — they don't

want to engage in drugged-out hippie psychedelia, and they don't want to fit

in with the Nashville crowds, but they are unable to work out a true new

musical genre that would take the best from both worlds, filter out the

excesses, and still manage to sound intelligent and emotionally exciting. And although

they'd have some time to sort it out later on, this is a problem that would

haunt the McGuinn/White era of The Byrds for their entire three-year period of

trying to fit in in a thoroughly changed musical world post-Woodstock and post-Abbey Road.

Wednesday, January 27, 2016

The Cardigans: Gran Turismo

THE CARDIGANS: GRAN TURISMO (1998)

1) Paralyzed; 2) Erase/Rewind;

3) Explode; 4) Starter; 5) Hanging Around; 6) Higher; 7) Marvel Hill; 8) My

Favourite Game; 9) Do You Believe; 10) Junk Of The Hearts; 11) Nil.

Well, things change. Although the band's fourth

record was made in the same Stockholm studio and produced by the same Tore

Johansson, the sound has definitely... evolved. There is a clear drive here to

make it more modern, by shifting a lot of emphasis over to electronics, drum

machines, and trendy trip-hoppy rhythms — forget the lounge jazz and retro-pop

of yesterday, here we are trying to peep through the window of tomorrow. Does

the music suffer? Hell yes, it does, although it also has to do with the overall mood in the studio: it's as if they

all spent way too much time listening to Portishead, and now all they can think

of are these slow, smoky, electronically enhanced grooves where atmosphere

counts more than melodic hooks. (Not that Portishead did not have their fair

share of melodic hooks — but if you are influenced by someone like that, first

thing you're gonna try to emulate is the texture, not the chord progressions).

Anyway, upon overcoming the initial

disappointment, once the bitter fog has cleared, it was quite a consolation to

understand that on the whole, the melodic skills of Svensson and Svenigsson did

not truly deteriorate (although, curiously, Svenigsson is credited only on two

of the tracks; most everything else is co-written by Svensson with Nina), and

that Nina's potential for seduction may be fully realized in an electronic

setting just as well. Maybe that unique Cardigans magic is really no more, but

this is still high quality pop music. I think most of the attention in 1998 was

diverted to the controversial music video for ʽMy Favourite Gameʼ (ooh, road

violence! blood! car crashes! censorship! real scary!); however, 1998 is long

past us and we are now free again to just enjoy the music without the outdated

MTV perspective.

ʽMy Favourite Gameʼ is actually a good song that

does not forget to incorporate a

strong hook, in the form of a nagging, «whimpering» three-note guitar riff that

agrees beautifully with Nina's melancholic vocals — although behind that generall

melancholy, there are few secrets to discover. The second single,

ʽErase/Rewindʼ, with a funkier, more danceable groove and an intentionally more

robotic vocal performance, was a slightly bigger hit in the UK, but it's

actually less impressive because it's so monotonous.

Actually, the best songs here tend to be the

slowest ones: they also take the most time to grow on you, but it is worth the

wait. ʽExplodeʼ, for instance — what a fabulous vocal part, where each accented

syllable is drawn out with so much eroticism, even if the lyrics do not

formally have much to do with sexual tension (more like "explode or

implode" is a metaphor for a drug addiction, though the lyrics are

deliberately ambiguous). Not much else by way of melody, but the somber organ

and the jangly guitar (or is that a harpsichord part? hard to tell with those

production technologies) provide a nice sonic blanket for the vocals. ʽHigherʼ

is formally classifiable as adult contemporary — but that's a really soulful,

sensitive adult contemporary chorus out there. It takes a special talent to

sing a line like "we'll make it out of here" so that it combines both

the optimistic hope of getting out of here and

the firm knowledge that we will never get out of here at the same time, and

Nina Persson does have it.

Electronics and adult contemporary aside, they

even managed to sneak a song here that would later attract the attention of the

Deftones — ʽDo You Believeʼ is not exactly nu-metal, but it rocks harder than

anything else on here, with industrial-style distortion of the riff and a

«brutal» coda where the soft-psychedelic echoing of the chorus contrasts with

the riff put on endless repetition. The lyrical message is the simplest on the

album — "do you really think that love is gonna save the world? well, I

don't think so" — and, as if in self-acknowledgement of the fact, it is

also repeated twice: yes, this whole record is about tragic endings,

disappointments, and disillusionments, and sometimes they are going to shove

it in your face quite openly. It's not very original, but it's honest, and as

long as they still got musical ideas to back it up, it's okay with me.

So yes, Gran

Turismo might essentially be qualified as Portishead-lite, but even if «lite»

rhymes with «shite», this does not mean they're identical. The downfall of The

Cardigans as a band with its own voice probably starts here, and as they add

ʽErase/Rewindʼ to their hit collection, the number of people who know them for

being providers of catchy, but faceless dance tracks begins to outnumber the

number of people who know them for being wonderful musicians. But album-wise,

in 1998 they were still playing a respectable game, so here is another thumbs up.

And as far as combinations of guitars and electronica in pop music are

concerned, this is still a lighter (and better) experience than, say, Madonna's

Ray Of Light.

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

Cactus: Restrictions

CACTUS: RESTRICTIONS (1971)

1) Restrictions; 2) Token

Chokin'; 3) Guiltless Glider; 4) Evil; 5) Alaska; 6) Sweet Sixteen; 7) Bag

Drag; 8) Mean Night In Cleveland.

If the idea of the album title is that Cactus

really knows no restrictions, I am sorry to say that they do, and that they are

the exact same restrictions that made their first two albums look idiotic even

in their most listenable moments. There are no attempts to change the formula

here: we are presented with a third platter of stiff, lumpy, leaden hard rock

where thickness of guitar tone, ferociousness of percussion attacks, and

loudness of lead vocalist matter much more than memorable melodies or, God help

us, spiritual depth.

When the experience is over, you will probably

want to ask yourself two questions: "Whatever made them rearrange Howlin'

Wolf's ʽEvilʼ as a Led Zeppelin II-style

rocker with a time signature that makes a confused mess out of the

vocals?", and "Is the idea of setting the lyrics of ʽSweet Little

Sixteenʼ to the melody of ʽRollin' And Tumblin'ʼ supposed to mean something, or

were they just randomly pulling out song titles out of a hat for a fortuitous

mash-up?" Not that it's important to know the answers, of course: ever

since the days of Vanilla Fudge, Bogert and Appice were the indisputable

champions of the «50,000 Ways To Ruin A Good Song» game, so why should Restrictions be an exception?

As for the original songs, there is not a

single one here that would be too memorable. The title track and the

never-ending ʽGuiltless Gliderʼ, taking up most of Side A, are the obvious candidates

for top pick, but ʽRestrictionsʼ refuses to come up with a decent riff, and

ʽGliderʼ is just too busy riding one rhythm chord for most of its duration

(interrupted by a drum solo, which is hardly a consolation). ʽAlaskaʼ quiets

down a bit for a jazzier take on the blues, some harmonica solos, and lyrics

like "I hear six months a year you get night time all day / I had to

practice my harp to keep the polar bears away", and it still sounds silly

rather than funny; and the final two minutes, called ʽMean Night In Clevelandʼ,

are just slow, simple acoustic blues.

The only thing that could redeem the whole

experience is the overall sound: the Bogert/Appice rhythm section is

impeccable, so much so that I would probably enjoy this record much more if all

the guitars and especially the vocals

were deleted. Truly, this is one of those moments when you start lamenting over the absence of corporate

songwriting — where the hell was Desmond Child when these guys needed him so

much? He probably could have helped them out even while still in high school. Thumbs down.

Monday, January 25, 2016

Buddy Guy: Blues Singer

BUDDY GUY: BLUES SINGER (2003)

1) Hard Time Killing Floor; 2)

Crawlin' Kingsnake; 3) Lucy Mae Blues; 4) Can't See Baby; 5) I Love The Life I

Live; 6) Louise McGhee; 7) Moanin' And Groanin'; 8) Black Cat Blues; 9) Bad

Life Blues; 10) Sally Mae; 11) Anna Lee; 12) Lonesome Home Blues.

Okay, so apparently «Sweet Tea» is the name of

the recording studio in Oxford, Mississippi, where Buddy made that album — and

also its follow-up two years later: an «other-side-of-me» companion piece, all

quiet and acoustic as opposed to Sweet

Tea's ferociously electric thunderstorms. On paper, this sounds like a

promising idea that could work: in fact, it does seem like a much better

proposition to replace the older sequence of «one kick-ass hard-rocking album,

one boring commercial album» with a more basic «one electric, one acoustic»

approach. Reality, however, turns out to be disappointing.

The thing is, Buddy Guy is not a great acoustic

guitar player — much like his late buddy Hendrix, his «native» sphere is the

electric guitar, where he experiments with tones, effects, feedback, and

dissonance. Switching to acoustic, he just plays it: plays the blues, that is,

like any averagely competent blues guitarist does (okay, make it «more than

average», but still, there's literally hundreds of guys who have the same kind

of acoustic technique and versatility as Buddy). Granted, the album is named Blues Singer, not Blues Player; but that hardly resolves the problem, since as a

singer, Mr. Guy is also competent and convincing, yet not exceptional.

And even that

is not the worst problem here. No, the worst is that for this record, Buddy

chooses a varied selection of old classics typically associated with specific

idols of the past — Skip James (ʽHard Time Killing Floorʼ), John Lee Hooker

(ʽCrawling King Snakeʼ), Frankie Lee Sims (ʽLucy Mae Bluesʼ), Muddy Waters (ʽI

Love The Life I Liveʼ), Son House (ʽLouise McGheeʼ), Lightnin' Hopkins (ʽBlack

Cat Bluesʼ), and a few other, somewhat lesser names; and instead of offering

the «Buddy Guy perspective» on all these guys, he pretty much tries to emulate every one of them. Excuse me,

but this is just stupid — as if he were some kind of Shang Tsung-like sorcerer,

having devoured all of their souls and exploiting them one at a time. He'd

committed such errors before, plenty of times, but never, as of yet, had any of

his records sounded like One Huge Error, stretched across fifty minutes' worth

of wasted time.

It almost goes without saying that outside of context — that is, if you are

not familiar with any of the originals — Blues

Singer sounds quite nice. It's not as if Buddy showed no understanding of

these tunes, or wasn't able to get a good grip on the melodies. It's even got a

few enticing bonuses, like both B. B.

King and Clapton offering guest solos on ʽCrawling King Snakeʼ (and it's not

every day that you get to hear B. B. play acoustic guitar, either, though you

can probably understand why upon witnessing his performance here). But why on

Earth should one settle for an imitation

of the real thing rather than the real thing itself? Unless your ears are

completely insensitive for old mono production, crackles and pops, or unless

you have made a vow never to listen to music that is more than 10 years old (in

which case, as of 2016, this album is already obsolete as well), Skip James

still does a better ʽHard Time Killing Floorʼ, because Skip James singing like

Skip James... well, I dunno, sounds a little more authentic, for some reason,

than Buddy Guy singing like Skip James.

The only reason why I do not think the album

deserves a «thumbs down» in the end is that, on the whole, it shows good vibes

and good will. Propagating the old classics is always worthwhile, and properly

crediting the songs to their creators (or, at least, their classic

interpreters) is a sign of honesty. Besides, an album that is competently

performed, well produced, and consists of mostly good songs should not be

called «bad» just because it is so utterly superfluous; and, after all, Buddy

is one of the last surviving «original carriers» of the tradition, so at least

it makes much more sense than if somebody like John Mayer came out with a

record like this. However, it is also a sign that «being an original carrier» never

guarantees top quality; and that being an old black bluesman from Louisiana

does not automatically place you on the same level of spirituality and

sensitivity as any other old black (dead) bluesman from Louisiana.

Sunday, January 24, 2016

Pink Floyd: Wish You Were Here (IAS #004)

The link to this week's Important Album Series review is here:

http://starling.rinet.ru/music/Great%20Albums/004_Pink_Floyd_Wish_You_Were_Here.htm

http://starling.rinet.ru/music/Great%20Albums/004_Pink_Floyd_Wish_You_Were_Here.htm

Saturday, January 23, 2016

Cabaret Voltaire: 1974-76

CABARET VOLTAIRE: 1974-76 (1980)

1) The Dada Man; 2) Ooraseal;

3) A Sunday Night In Biot; 4) In Quest Of The Unusual; 5) Do The Snake; 6) Fade

Crisis; 7) Doubled Delivery; 8) Venusian Animals; 9) The Outer Limits; 10) She

Loved You.

Now that the band was a firmly established

underground act, the time was deemed ripe for digging into their back catalog

— they'd made their first recordings in the mid-Seventies, but had neither a

proper distributor back then nor a lot of people who'd listen. Actually, even

in 1980 the only label that'd carry this stuff was the Throbbing Gristle-owned

Industrial Records, who only released it in cassette form; not until 1992 did

it get a CD release.

And I don't have to tell you the reason why —

this stuff is far more hardcore than even Mix-Up,

let alone everything that followed. These, indeed, are industrial experiments

that predate the band's fascination with dance music, meaning that you are

going to get the same bleeps, beeps, bells, and whistles, but with a «factory

setting» rather than «club setting». Actually, there is a rhythmic base to most

of the tracks, either provided by a very faintly ticking drum machine or by the

synthesized «melody loops» themselves — the only thing that provides some

structure and order — but it does take a fairly wide understanding of music to

agree that this is music (not that it

is in any way more hardcore than Throbbing Gristle, but it does make everything

they'd done after that look like a pathetic sellout program by comparison).

A few of the tracks do dig into the musical

past, posing as sneery deconstructions or futuristic tributes: ʽDo The Snakeʼ

plays like a robot-engineered parody on an early Sixties dance craze (although

the mock-idiotic vocals are more in the vein of the B-52's: apparently, at that

early hyper-experimental stage Cabaret Voltaire still had a lighter sense of

humor than in the classic days to come), and ʽShe Loved Youʼ recites the lyrics

to ʽShe Loves Youʼ in a slow, dark whisper, as the electronics hum and whirr

around you with the predictable reliability of old, creaky equipment in an antiquated

factory.

Does it all make sense? Not to my ears, it

doesn't. But it does sound like a

logical precursor to Autechre and all those other trendy Nineties' electronic

bands — whose main achievement, let's face it, was to simply harness the

technology in a way in which Cabaret Voltaire in the mid-1970's could not have

harnessed it, without all that comfy digital software. They do try their best:

many of these tracks are quite inventive, with lengthy stretches of attempted

development as synthesized tones pulsate, grumble, burp, whine, explode,

implode, chase each other and fade away on some of the ugliest frequencies

you've ever heard (ʽIn Quest Of The Unusualʼ — indeed; ʽThe Outer Limitsʼ — two

minutes of shrill ear-destruction and six more minutes of either a rusty metal

fan twirling around or broken automatic doors closing and opening). But, as

usual, there may be problems afoot when you start thinking of this as Art, and

looking for those particular doors of perception that may or may not have been

opened by your exposure to it.

At least on a purely objective basis this stuff

seems innovative in the context of the time, when electronics were still

largely used as a replacement for traditional instruments rather than a means

to completely redefine our approach to music — something in which Cabaret

Voltaire had a very active hand. But they didn't even hold on to this style for

very long: much like Kraftwerk, whose least accessible records were their

earliest ones, by the time they'd gotten a record deal they were already

willing to compromise. And although I am not quite sure this made their music

«better», I am at least grateful to them that they decided to make

«dance-oriented» (sort of) tunes out of these factory puffs and huffs, instead

of retaining their throbbing gristly integrity for the remainder of their

career.

Friday, January 22, 2016

Budgie: Impeckable

BUDGIE: IMPECKABLE (1978)

1) Melt The Ice Away; 2) Love

For You And Me; 3) All At Sea; 4) Dish It Up; 5) Pyramids; 6) Smile Boy Smile;

7) I'm A Faker Too; 8) Don't Go Away; 9) Don't Dilute The Water.

A brief, if somewhat half-assed, return to hard

rock quality here. Perhaps they realized that Brittania took things a little too far and placed them in danger

of completely losing whatever little bits of identity they had. In any case, Impeckable rocks with more energy and

has somewhat better riffs — but that's about it, then: not a single song has

the stunning power of a ʽBreadfanʼ or the viciousness of ʽIn For The Killʼ.

Which is too bad, because some stunning power and viciousness would have fit

in very well with the look on the face of that black cat on the cover. Wait a

minute, though... the cat is aiming for the budgie, right? So what is this, a

hint at the dark hand of fate poised to tear the band in two?

As in some other cases as well, the best songs

here are probably the first and last tracks. First one comes on as a strong

imperative (ʽMelt The Ice Awayʼ), boogies like crazy, and builds a nice

descending ladder in the chorus, while Bourge tries on Angus Young's

speed-choked soloing style for a change. Last one is a prohibitive (ʽDon't

Dilute The Waterʼ) has some well constructed sectional transitions and arguably

the best riff on the album (there are several, actually, but you'll know the

one when you hear it), providing us with at least one «snappy» moment (meaning

that you'll actually be feeling the guitar attacking you, lashing out at your

heels, rather than just doing its independent shtick somewhere out there in the

atmosphere).

In between... well, some of the songs are

really strange, like ʽLove For You And Meʼ, where the verse sounds like a

preview of late period AC/DC (slow lumpy leaden riffage) and the chorus borrows

its formulaic soulfulness from Foreigner; or like ʽDish It Upʼ, where they once

again make the mistake of descending into funky territory. But the power ballad

ʽAll At Seaʼ is surprisingly not bad, with tasteful, lovely, melancholic

harmonies in the chorus; and the return to acoustic guitars and falsetto

harmonies on ʽDon't Go Awayʼ seems to me to be more successful than ʽRiding My

Nightmareʼ from their best album.

Still, it is clear that re-embracing the past

is no longer an option for these guys: something went wrong, and now it is as

hard for Bourge to stay sharp and inspired as it was for his senior pal Iommi

that very same year (Sabbath's Never Say

Die alos showed a sharp drop in quality — was it really the wind of change,

or, more accurately, the New Wave of change that kicked the ground from under

all these old heavy rockers' feet around 1978?). Even the best songs meander,

and it never feels as if the players believe in themselves and their mission. At

least Tony certainly did not: right after the album was released (and flopped),

he quit the band for good.

Essentially, Impeckable was released at a turning point for the heavy metal

scene — the old school ideas were running out of steam, and the New Wave hadn't

quite kicked in yet, let alone the speed and thrash idioms. On the other hand,

since the «refreshed» Budgie of the 1980's never truly managed to make a

respectable transition to the new values, a half-hearted, meandering,

transitional record like this is still preferable to whatever happened when Mr.

Shelley switched his role model from Black Sabbath to Judas Priest. Seen from

that angle, ʽDon't Dilute The Waterʼ is at least a fitting swan song for the

classic era of this band.

Thursday, January 21, 2016

The Byrds: Sweetheart Of The Rodeo

THE BYRDS: SWEETHEART OF THE RODEO (1968)

1) You Ain't Going Nowhere; 2)

I Am A Pilgrim; 3) The Christian Life; 4) You Don't Miss Your Water; 5) You're

Still On My Mind; 6) Pretty Boy Floyd; 7) Hickory Wind; 8) One Hundred Years

From Now; 9) Blue Canadian Rockies; 10) Life In Prison; 11) Nothing Was

Delivered.

The sweetheart in question turned out to be

male: Mr. Ingram Cecil Connor The Third of Winter Haven, Florida, better known

as Gram Parsons, the father of country-rock and a respectable member of Club

27 (26, to be more precise). Although he was originally recruited by The Byrds

as a keyboard player (to play jazz piano, no less!), he soon moved to guitar,

then to songwriting, then to musical ideology, and, according to some sources,

ended up nearly wrestling control over the band from McGuinn; when that failed,

he quit in protest over the band's touring engagements in apartheid-rule South

Africa — though some suspected it was largely just a pretext. You never know

for sure with these things, anyway.

We all know the drill: McGuinn wanted the next

Byrds album to be a sprawling overview of all the genres of American pop music,

from the early days and well into the future, but abandoned the project — due

partly to the lack of a proper budget and support from the rest of the band,

and partly due to Parsons' insistence to turn specifically to country. Spilling tears over Roger's unrealized

project is useless, since we do not even know whether he was properly qualified

for this; but neither would I agree to succumb to waves of critical respect for

this album. Released in August 1968, it marked a sharp commercial decline in

the band's fortune. Rock audiences of the time were not prepared for any

radical «country twists», and although The Byrds weren't really doing anything

that their major idol, Mr. Zimmerman, hadn't already done with John Wesley Harding and those parts of

the Basement Tapes that were already circulating among devotees, their wholesale

conversion to the Nashville spirit was not greeted with too much pleasure by

record buyers, even if critical reviews seemed to be relatively benevolent.

The historical status of Sweetheart Of The Rodeo — the first LP release by a major

established «pop/rock» artist to consistently,

rather than sporadically, embrace the country idiom, and without any traces of

irony at that — is indisputable, as is its social importance: a sincere attempt

to bridge the gap between the rural and the urban, the conservative and the

progressive, the hillbilly and the hippie. The Byrds may have gotten their fair

share of flack for this gesture, from both the hillbilly and the hippie side, but this is the predictable fate of all

fence-sitters, sacrificing themselves while gambling on humanity's future.

What matters far more is how well the record holds up after all these years —

and this is where I continue to have my doubts.

Curiously, it does continue to have its fanbase among the rockers, usually along

the lines of "well, I'm not much of a country fan, but I have nothing

against country if it's done right,

and this is one such case". Well, the thing is, I'm not sure how this here

version of ʽLife In Prisonʼ is done more

right than Merle Haggard's; or how this particular performance of ʽYou're Still

On My Mindʼ carries more energy and excitement than George Jones' rendition of

it. The Byrds pick a solid set of tunes — as far as country goes, these songs

mostly have interesting vocal hooks, though the base melodies are predictably

generic waltzes and shuffles. McGuinn, Hillman, and Parsons sing the tunes with

enough conviction, guest guitarist Clarence White does the Nashville shtick

with gusto, it's all fine and dandy, but... ultimately, it's just a cover album

of country tunes.

Sure there are a few originals, mostly courtesy

of Parsons, but I have never understood and still do not understand the

adoration for ʽHickory Windʼ, a song whose compositional virtues amount to

precisely zero (it is just a regular country waltz), lyrical virtues consist of

clichés ("hickory wind keeps callin' me home" is not exactly a

breakthrough in country lyricism), and musical arrangement is not

fundamentally different from similar arrangements for hundreds of country songs

(fiddles, slide guitars, honky tonk piano, you know the drill). The only thing

standing for it is Parsons' presence, I guess — if you are enchanted by the man's

lonesome-hero charisma — but it's not as if he had a totally unique singing

voice or presence, either. For my money, his other original, ʽOne Hundred Years From Nowʼ, beats ʽHickory Windʼ

on all counts — less obvious vocal melody (the verse melody actually pinches a

bit from ʽGod Only Knowsʼ, don't you think?), psycho-folk harmonic singing from

McGuinn and Hillman, and overall, a clever mixture of folk, country, pop, and

psychedelic elements.

Ironically, the Byrds are still at their best when they rely on the tried and true — covering

Dylan, that is. ʽYou Ain't Going Nowhereʼ, a perfect opener for the album, does

the usual wonder of converting Bob's natural ugly beauty into smooth-glamorous

pop perfection, with there being enough free space in the world to allow for

both visions. Here, we have the most heartfelt and sensitive McGuinn vocal

performance on the album, and a vivacious, elegantly woven steel guitar lead

melody as his lovin' partner throughout the song, and those "ooh-wee, ride

my high, tomorrow's the day my bride's gonna come" harmonies are a

downright epitome of tenderness itself. Basically, they took a Dylan song that

began life as an absurdist ode to nihilism and turned it into an optimistic

love anthem, while still retaining some of that absurdism. And then, in a

sudden fit of symmetry, they close out the album with a bitter reversal of

these feelings — having started out with "get your mind on wintertime, you

ain't going nowhere", they end the record on "the sooner you come up

with it, the sooner you can leave" (ʽNothing Was Deliveredʼ) and a sort of

disillusioned atmosphere (which, incidentally, is also how I feel about this record).

The problem is, they know how to reinvent

Dylan, but they never had a good idea about how to reinvent Woody Guthrie,

Merle Haggard, or Cindy Walker — they just cover

them, retaining the original spirits of these songs. The whole point of Sweetheart Of The Rodeo is to shock the audiences along the lines

of "see, we're rockers, but we're doing country, how unusual is that?": this attitude was even

incorporated into the promotional campaign, as you can see from the original

radio promotion bit, hidden at the end of the last bonus track on the CD

reissue — as bits and pieces of songs flow out of the speaker, a girl and a guy

argue with each other: "It is

the Byrds! — That's not the Byrds... — Okay, listen to this one! See, it is the Byrds! They're playing Dylan! —

It can't be the Byrds! Play another one... — It's the Byrds all right! — Nah,

that ain't the Byrds..." I regret to say that sometimes it seems to me

this radio bit carries more fun with it than the majority of the record itself.

Anyway, these are mostly decent tunes (though

lyrically, ʽThe Christian Lifeʼ is atrocious, and McGuinn must have lost plenty

of credibility with his friends for that one), and only people with a very

strong anti-Nashville bias could hate

Sweetheart Of The Rodeo. But shuffle

these tunes around a bunch of top (or even middle) quality country albums, and

if there's some way in which they will notably stand out, let me know. As far

as I'm concerned, Sweetheart is an

ideological gesture first, and a

collection of musical pieces second —

which doesn't do much for a record in the long run. Interesting and curious,

yes, not without its few moments of Dylanesque glory, yes, but essentially the

band just shot itself in the foot with this one, and ended up hobbling for the

next three years of its existence.

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

The Cardigans: First Band On The Moon

THE CARDIGANS: FIRST BAND ON THE MOON (1996)

1) Your New Cuckoo; 2) Been

It; 3) Heartbreaker; 4) Happy Meal II; 5) Never Recover; 6) Step On Me; 7)

Lovefool; 8) Losers; 9) Iron Man; 10) Great Divide; 11) Choke.

This is the one that has ʽLovefoolʼ on it — the

song that made the band in the eyes

of mass European and American audiences, because, let's face it, if there is a

pop-rock band that consists of several male musicians and one blonde female

singer, it's Blondie, right? But no band is really Blondie until it has a

genuine Blondie mega-hit, and so ʽLovefoolʼ was selected by mass tastes as

their ʽHeart Of Glassʼ, with which it does share some things in common: the

light-headed, bitter-hearted attitude, the disco danceability, the funky riffs,

the sweet sweet catchiness. And it's a nice song alright, but for someone like

me, who totally missed it in the Nineties, it is not even the best, or the most

memorable song on this album, let alone in the Cardigans songbook as a whole.

Even without ʽLovefoolʼ, you could tell that

the band is trying to modernize its sound here: ʽYour New Cuckooʼ opens things

up with a strong neo-disco beat, and throughout the album there are plenty more

signs of moving away from the relaxed, folk- and jazz-influenced atmospheres of

the first two albums and into more dance-oriented, contemporary territory.

However, this troublesome «commercialization» is only superficial. Not only

are the actual melodies as strong as ever, but the band's bittersweet romance attitude,

as personified by Nina's singing technique, remains exactly the same as it used

to be. Consequently, this is one of those rare cases where a sellout is not

really a sellout — it is simply a matter of becoming able to sell precisely the

same thing that, earlier on, you were not able to sell. For technical,

unimportant reasons.

Besides, other than ʽLovefoolʼ and ʽYour New

Cuckooʼ (whose saccharine disco chorus is admirably turned into a

tongue-in-cheek expression by Nina's sarcastic "let's come together, me

and you... your new cuckoo" delivery and the grumbly guitar riff), the

only number presented as a modern dance track (slow trip-hop style) is, would

you know it, another Black Sabbath

cover. Unlike ʽSabbath Bloody Sabbathʼ, which they really nailed — unveiled, in

fact — as the sentimental pop song that it had always been in the first place,

this take on ʽIron Manʼ is less successful. They do a good job jazzifying the

classic riff, and Nina's scat singing on the outro is hilarious (especially

when she does that little «scratching turntables» routine), but the lyrics just

don't fit in. More like ʽGingerbread Manʼ than ʽIron Manʼ, if you know what I

mean. No purpose to it, really, other than a "let's really go down in history like that crazyass Sabbath cover

band" sort of statement. Which, on the other hand, is also respectable in

its own strange way.

But then there's just lots and lots and lots of

other good songs on top of this.

ʽNever Recoverʼ is a fast, upbeat, snappy post-Beatles / post-Bangles power-pop

gem, with a resplendent chorus full of energy and sunshine. ʽBeen Itʼ should be

primarily respected for the

sexy-seductive instrumental and vocal melody of its chorus, and only

secondarily for the lyrics ("ooh, she calls herself a whore! that's so Madonna! this is, like, disturbing!") — actually, she makes bitter fun of former lover

boy rather than degrading herself, and all the guitar riffs sound like whips

across poor unfortunate male skin and flesh. Did I ever use the word

"misandrist" yet in a review? Probably not; well, 1996 seems like the

right time to start.

Slow, moody, haunting tunes? Yes, still plenty

of them. The pretty moonlight waltz of ʽHeartbreakerʼ. Lounge sounds still pursue

us with ʽGreat Divideʼ (chimes, strings, treated guitars, tempo changes, mood

changes — there's quite a lot going on in these three minutes). ʽChokeʼ,

closing the album, is impossible to describe in genre terms: it combines

elements of alt-rock, R&B, and jazz, and on top of it, there is the riff from ʽIron Manʼ! Somehow, it slipped and fell

through the cracks, landing on top of the final track and finding it

comfortable enough to stay there. Gee, these whacky rover riffs.

As you can understand, this is yet another

major thumbs up:

the band's third melodically strong, atmospherically captivating, technically

inventive album in a row. And I'm sure that, as long as you do not associate

it exclusively with ʽLovefoolʼ, you'll be all right.

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

Cactus: One Way... Or Another

CACTUS: ONE WAY... OR ANOTHER (1971)

1) Long Tall Sally; 2)

Rockout, Whatever You Feel Like; 3) Rock'n'Roll Children; 4) Big Mama Boogie,

Pts. 1 & 2; 5) Feel So Bad; 6) Song For Aries; 7) Hometown Bust; 8) One

Way... Or Another.

If the band's first album at least had its

share of dumb fun, then the second one is not even fun any more. Stiff, lumpy,

humorless, and hookless, these guys make me feel that I have really underappreciated KISS for all

these years. It is not a crime to set your artistic ambitions real low and just

make a danceable rock'n'roll album for the sakes of partying all night long;

however, it takes some true «anti-talent» to make a rock'n'roll album that

would not only be completely dispensable the morning after the party, but

would also cost you at least half of your party guests.

Because, honestly, no respectable party goer

would ever agree to accept the fact that ʽLong Tall Sallyʼ is now to be played

about three times as slow as the original — trying to retain the enthusiasm

and hysteria of Little Richard, but slowing down to a veritable crawl. It's as

if some nasty schoolmaster snuck into the party at the last minute and told them

to go slow, under threat of expulsion — forgetting all about the other

parameters because they were more difficult to formulate. It's innovative, for

sure... and utterly ridiculous. As is the equally slow and stiff ʽFeel So Badʼ,

which was far sexier when a post-army Elvis did it in the early Sixties.

It is not altogether clear to me who'd fall for

this stuff in 1971: the best heavy metal bands were busy trying to peer into

the future, whereas Cactus here clearly remain chained to the standards of

1969. The only detours from the formula are on ʽBig Mama Boogieʼ, which does

try to boogie, John Lee Hooker-style (but on an acoustic guitar!) for about

four minutes, without too much confidence, and then makes the plunge into true

kick-ass electric boogie for about one more minute, by which time, however, we

are probably way too bored to pay any attention; and then there's the

never-ending ʽHometown Bustʼ, a long, dreary, overdone complaint about the

ongoing drug busts (as if this could help where even Steppenwolf could do

nothing). Oh, and a three-minute pastoral instrumental (ʽSong For Ariesʼ) where

the guitarist experiments with echoes, Leslie cabinets, and overdubs, balancing

somewhere on the edge of prettiness but never quite getting there.

Ultimately, this just sounds like a very, very,

very boring record to me. If it were at least «comically bad», as in the case

of KISS, if they went nuts and posed as Gods of Thunder or as Lord Protectors

of Cock-and-Balls Music, you could be in it for the cheap thrills. But

listening to ʽLong Tall Sallyʼ being played that

way is like... well, like having to attend a ninety-minute lecture that could

be summed up in thirty seconds. Maybe they're taking their cues from Led Zeppelin

alright, but Led Zeppelin were never Led Bathyscaphe — they did know how to

soar and zap through the atmosphere despite all the heaviness. These guys just

lumber on. No fun whatsoever. A totally depressed thumbs down — and I like simple, stupid rock'n'roll music

when I can get it. But this just ain't it.

Monday, January 18, 2016

Buddy Guy: Sweet Tea

BUDDY GUY: SWEET TEA (2001)

1) Done Got Old; 2) Baby

Please Don't Leave Me; 3) Look What All You Got; 4) Stay All Night; 5) Tramp;

6) She Got The Devil In Her; 7) I Gotta Try You Girl; 8) Who's Been Fooling

You; 9) It's A Jungle Out There.

I have no idea what the title is supposed to

symbolize (was "sweet tea" the finest taste to be tasted by a young

Buddy during his early Louisiana days?), but the album is indeed Buddy's finest

in a long, long while. It continues the strange pattern of alternating a

rougher-edged, more aggressive and inventive record with a softer, calmer, more

commercial one — but there's something extra special here that was not seen

either in Damn Right or in Slippin' In, the two real good 'uns.

Perhaps it's his new band, now including Davey Faragher of Cracker on bass and

Jimbo Mathus of Squirrel Nut Zippers on second guitar, that gives Sweet Tea its edge — at the very least,

I can definitely vouch for Faragher as far as the bass goes, because this is

the first time we have such a deep, echoey, rumbling bass sound on a Buddy Guy

album, and I love it.

More generally, though, Sweet Tea sounds like it's out there to say something, not just to

show the world that Buddy Guy is still playing the blues. The first track is a

consciously laid trap — an acoustic moanin' blues, courtesy of the

then-recently deceased Junior Kimbrough, on which Buddy laments that he

"done got old" and that he can't look, walk, or love "like I

used to do", in the general fashion of an old Negro spiritual. Of course,

that's a ruse — already the second track, the lengthy, slow, threatening ʽBaby

Please Don't Leave Meʼ shows that getting old sure don't prevent Mr. Guy from

playing God of Thunder if he sets his heart to it. That great psychedelic

distorted tone is back, and coupled with Faragher's doom-laden bass sound, it

gets the old mojo workin' — the entire seven minutes seem like a voodooistic

ritual performed by the man to ensure that his baby don't leave him. And who

could, after such a performance?

A few tracks down the line, he tries to repeat

the exact same ritual with the even longer, but less effective ʽI Gotta Try You

Girlʼ — same bass, same tempo, same style of vocal incantation, but a little

less fury and a little more plodding with the solos; also, in this modern age

endless repetition of the lines "I gotta try you girl, we gotta make love

baby, no matter what you say girl" could get you arrested in some parts of

the country, but I guess this could probably never stop a real man like Mr.

Guy. Still, for about five or six minutes the ceremony can be just as breathtaking

as its shorter and angrier predecessor.

I am not going to launch into a detailed explanation

of the other tunes, of course — suffice it to say that there are many more

covers of the late Junior Kimbrough here, as well as some other blues pals of

Buddy's (CeDell Davis, Lowell Fulson, etc.), and only one «original» (ʽIt's A

Jungle Out Thereʼ, yet another bit of socially-conscious preaching on Buddy's

part that sounds like an imagination-less sequel to ʽCities Need Helpʼ). The

important thing are not the individual tunes, but the overall sound of the

album — that bass, that echo, that renewed ferociousness on those sharply tuned

guitars, well, it's not exactly a revolution, but it is the hugest and

brutal-est update of the Buddy Guy sound ever since the underrated Breaking Out experiment in 1980. And,

funniest of all, it is a huge f*ck-you to all those new generations of blues

players. Who would be the very first blues musician to come out with a solid

update of the blues idiom in the 21st century? A 65-year old native of Lettsworth,

Louisiana, that's who. Now let us see you top this, Mr. John Mayer. Thumbs up.

Sunday, January 17, 2016

The Velvet Underground: The Velvet Underground & Nico (IAS #003)

This week's Important Album Series update is up:

The Velvet Underground: The Velvet Underground & Nico

The Velvet Underground: The Velvet Underground & Nico

Saturday, January 16, 2016

Cabaret Voltaire: The Voice Of America

CABARET VOLTAIRE: THE VOICE OF AMERICA (1980)

1) The Voice Of America /

Damage Is Done; 2) Partially Submerged; 3) Kneel To The Boss; 4) Premonition;

5) This Is Entertainment; 6) If The Shadows Could March; 7) Stay Out Of It; 8)

Obsession; 9) News From Nowhere; 10) Messages Received.

A little better produced than Mix-Up, perhaps, but not much different

in mood, style, or effect, The Voice Of

America is a fairly distorted idea of America, I would say, as seen from

the perspective of this ever-so-English band. If we are to believe in this,

«America» in 1980 was a post-apocalyptic half-bore, half-nightmare, a gray,

desolate place populated almost exclusively by robotic mutants communicating

through digital signals and tape loops. There would hardly be any place for a

Prince or a Michael Jackson or even an Olivia Newton-John in such an America —

then again, we could always make the argument that Cabaret Voltaire, with their

eye in the sky, were able to see right through all these skins and quickly get

to the essence.

Anyway, The

Voice Of America is not nearly as unlistenable as some sources would have

you believe. Ever so often, a track will start out with a blast of noise that

seems to be coming out of a freshly bombed electrical substation — but then it

quickly subsides in favor of yet another cozy little robotic groove, going

pssht-pssht (that's «C.V. soft rock») or thwack-thwack («C. V. hard rock») or

twang-twang (that's «C.V. impersonation of Australian aboriginal music»), with

enough diversity to keep you believing that it is not the exact same

psycho-image that never stops flowing through their brains while they're busy

getting on tape. Whether this is a correct belief, I am not sure — in the end,

all these recordings still seem to serve the same purpose.

The band only becomes truly unlistenable when

it abandons its rhythmic base to make room for some free-form improvisation —

ʽPartially Submergedʼ sounds like a rusty old see-saw swinging back and forth,

while a pair of aspiring, but tonedeaf sax players are practicing like mad

within the confines of the same abandoned playground. Not as nasty as it could be, but I can promise you some

fairly ugly sounds here; the rest of the record is far more musical, sometimes

even hummable, even if you have to wait to the very end to get to the only

actual «song» — ʽMessages Receivedʼ. That one would seem to be a conscious imitation

of classic Joy Division style, but with shitty distorted guitar noise replacing

discernible melody.

Everything else is mildly cool — somewhat tame

by the old Krautrock standards, and frequently spoiled by the vocals (I think

the album would have worked better as a completely instrumental set, but I

guess those brutal «young punk» intonations were very much a genre convention

around 1980), but not without its own bit of decadent-robotic charm. However,

you can still feel they are in their boot camp stage at the moment: they have

the style all figured out, but none of the compositions have any sense of

purpose — mostly, it's just experimentation for the sake of it, a useful, but not

too artistically relevant exploration of new studio possibilities. For

instance, on ʽNews From Nowhereʼ they discover that they can imitate racing

cars with their instruments, and then proceed to do exactly that for two and a

half minutes, like little kids who just discovered a bunch of awesome buttons.

Kinda cool, but that's what the word «dated» is for. Another short track is

called ʽIf The Shadows Could Marchʼ — to be honest, sounds more like ʽIf The

Shadows Could Trotʼ, but there's no sense in arguing over associative thinking;

the important thing is, it's fifty-five seconds of not-too-threatening

electronic pulses, and that's that.

The good news is that most of the stuff, as

usual, is danceable, and even today you could safely use this stuff at any electronic

rave party with a retro fetish. But the bad news is that even with all the

grooves and the toe-tapping, they are still boring, and their appeal is at best

purely intellectual. Unless you make a point of collecting early Eighties'

electronics and avantagarde stuff, The

Voice Of America is perfectly skippable.

Friday, January 15, 2016

Budgie: If I Were Brittania I'd Waive The Rules

BUDGIE: IF I WERE BRITTANIA I'D WAIVE THE RULES (1976)

1) Anne Neggen; 2) If I Were

Brittania I'd Waive The Rules; 3) You're Opening Doors; 4) Quacktor And Bureaucrats;

5) Sky High Percentage; 6) Heaven Knows Our Name; 7) Black Velvet Stallion.

Budgie's first serious misstep on the road to

oblivion — and what makes matters sadder is realizing that this was not even

an intentional commercial sellout, but rather a confused, uncertain attempt to

branch out and experiment without any clear understanding of where they were

going and why they were going there. Alas, some people are born to make their

mark in many places, but some should rather stick to set formulae. Imagine

AC/DC trying to play James Brown-style funk or Canterbury-style progressive

rock — this is not exactly what

happened to Budgie on this album, but it comes close.

The title track here, for instance, is a real

mess. Opening up with a decent enough metal riff, it quickly dispenses with it

in favor of a light, wimpy funk groove alternating with boring folkish

arpeggios, then eventually slips into disco territory, with Shelley in

full-fledged Studio 54 mode and Bourge previewing the Nile Rodgers style; all

that's missing is some of those disco strings to complete the picture. Not that

there's anything wrong by default

with Budgie playing disco, but this particular section seems to exist only for

the sake of contrast with the opening heavy metal bits — and it's a rather

meaningless contrast, frankly. All the song does is waste a potentially good

pun on a stupid musical synthesis where the individual parts exist only for the

sake of a collective effect, and the collective effect is best described as

"what the..."?

Worse, they are beginning to lose it even when

staying in more familiar territory. ʽAnne Neggenʼ, opening the album, is an

honest rocker, but they probably had so much fun shaping a mondegreen from the

refrain ("and again, and again, and again...") that they not only

forgot to throw in a good riff, but did not even bother to bring the track up

to their esteemed standards of heaviness — Bourge plays almost the entire song

as quietly and cautiously as if he were afraid to wake up the neighbours. In

the past, all of their albums started

out with impressive heavy openers (ʽGutsʼ, ʽBreadfanʼ, ʽIn For The Killʼ, etc.)

that immediately set a sympathetic tone for the entire album; ʽAnne Neggenʼ

immediately sets the wrong tone, as

if we are being introduced to a forced change of musical diet for health

reasons.

As we go further and further, corrections to

these mistakes are not being made.

The ballad ʽYou're Opening Doorsʼ sounds like another preview — to bad

Foreigner. ʽQuacktor And Bureaucratsʼ at least starts out with a thick, distorted

tone for the rhythm guitar, but hopes for something crunchy and snappy are

quickly dissipated as the song proves to be a fairly (sub-)standard baroom

rocker with totally predictable chords and no musical development whatsoever.

ʽSky High Percentageʼ is a generally okay, but unmemorable piece of boogie, and

the second ballad just completely passes me by.

In the end, there is exactly one song worth

salvaging off the album: ʽBlack Velvet Stallionʼ somehow succeeds as an epic

piece despite the melody hanging upon a four note syncopated bass/rhythm guitar

riff throughout, the kind of phrase that tends generally to be used for transitions

from one section of the song to another. However, Shelley manages to inject a

good dose of the old «Budgie sorrow», and Bourge finally gets a chance to

unleash some inventive soloing, going from minimalist, almost ambient mode into

a series of scorching bluesy licks and then building up to an awesomely

climactic coda. What exactly prevented them from featuring the same level of

intensity on all those other songs, I

have no idea.

Usually, when trying to explain such failures,

people pronounce the word «drugs» (which is a great universal key to everything — as we know, both the

greatest music ever and the shittiest

music ever always owe their success/failure to drugs), but I don't even know if

drugs were involved in the first place. More likely, they just said to

themselves at one point, "Hey! We're doing great, but it's all because we

have awesome riffs and guitar solos. Why don't we show them how great we can do

if we toss away the awesome riffs and guitar solos? If we were Brittania, we'd

waive the rules, you know!" I almost hate to be giving this a thumbs down,

because deep down inside, I respect failed experiments, but these failed

experiments aren't even particularly fun to listen to for the sake of

understanding where and how they failed. And one good song out of seven, coming

on as a comforting bonus for your patience, does not count for much.

Thursday, January 14, 2016

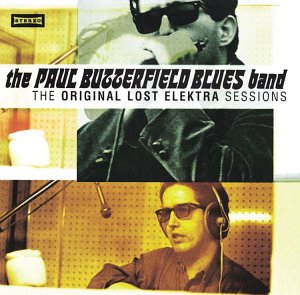

The Butterfield Blues Band: The Original Lost Elektra Sessions

THE BUTTERFIELD BLUES BAND: THE ORIGINAL LOST ELEKTRA SESSIONS (1964/1995)

1) Good Morning Little Schoolgirl;

2) Just To Be With You; 3) Help Me; 4) Hate To See You Go; 5) Poor Boy; 6) Nut

Popper #1; 7) Everything's Gonna Be Alright; 8) Lovin' Cup; 9) Rock Me; 10) It

Hurts Me Too; 11) Our Love Is Driftin'; 12) Take Me Back Baby; 13) Mellow Down

Easy; 14) Ain't No Need To Go No Further; 15) Love Her With A Feeling; 16)

Piney Brown Blues; 17) Spoonful; 18) That's All Right; 19) Goin' Down Slow.

Although the posthumous legend of The

Butterfield Blues Band mainly lingered on in circles of «aficionados» and

«connaisseurs», it was strong enough to trigger a large series of archival releases

in the mid-Nineties — and for understandable reasons: most of these releases,

like Strawberry Jam or East-West Live, were culled from live

shows recorded while Bloomfield was still in the band, so as to satisfy the

demand for Mike-era live material and have something to commemorate the band's

finest incarnation on stage, rather than its latter day version with the brass

players replacing the original guitarists. Unfortunately, all of these releases

are bootleg quality: for some reason, the original band did not care much about

being recorded professionally while in live flight, and most of this stuff is

barely listenable, let alone reviewable.

In the end, the only archival release by the

original band that is worth owning and talking about is the very first one —

their failed first attempt at recording an LP, which they made as early as December

1964, immediately after signing up with Elektra. Not all of the 19 songs

included here date from those very sessions, but most of them do, and since the

band was already fully formed and included Bloomfield, and the recordings were made in a professional studio, this here is

an indispensable acquirement for The True Fan.

The problem is, I can sort of see why the

people at Elektra were not impressed. From a certain angle, these covers of

classic blues and R&B numbers are not significantly different from the

contents of The Paul Butterfield Blues

Band — indeed, a few would later be re-recorded for that very album. The

subtle difference is that in late 1964, this really was «The Paul Butterfield Blues Band», with Paul's vocals and

harmonica always taking center stage and always being much higher in the mix

than everything else. Basically, ladies and gentlemen, we come here to listen

to the amazing Mr. Paul Butterfield do impersonations of Muddy Waters, Howlin'

Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson II, Elmore James, and particularly Little Walter —

and there are a few sidemen playing, uh, on the sides, but they're quite

dispensable.

There are only a few spots where Bloomfield is

allowed to shine, and they're cool and important: instrumental rave-ups like

ʽNut Popper #1ʼ and R&B dance numbers like ʽLovin' Cupʼ are probably the

earliest known examples of the classic Bloomfield style, and even a small

handful is enough to say that for that brief moment in late 1964 / early 1965,

Mike Bloomfield may have been the coolest axe player in the West, and the only

real competition to Mr. Slowhand of the Yardbirds' fame as the finest (white,

at least) blues-rock guitarist known to mankind. But it is a really, really small handful — and it betrays

jealousy, since on ʽMellow Down Easyʼ, for instance, Butterfield does not even

allow him a proper solo: all the lead parts are played in the background and

convenietnly muffled by the much louder harmonica parts. (On the 1965

re-recording, that would change, and Mike would get to slip in something purely

his own).

To serious admirers of Paul's harmonica-blowing

talents, this should not be a disappointment; on the contrary, I'd say that not

a single «proper» BBB album features as much harmonica playing as these early

tapes — where Paul is simply all over the place. But honestly, unless you

really, really take your time thinking about how to use your harp in various

creative / expressive ways, depending on the structures, tonalities, moods of

the individual songs, a blues-rock «Listen To Me Blowing» type album is

ultimately bound to sound boring, and I can suggest that the people at Elektra

thought so, too. As competent as these covers are, Butterfield here is the

all-pervasive imitator, and only Bloomfield is the occasional innovator —

because at least several Chicago blueswailers played better harmonica than Paul

(let alone singing), but no Chicago lead guitar players ever played a guitar

solo the way Bloomfield does it here on that ʽNut Popperʼ thing.

For some reason, many accounts of the album try

to increase its status by claiming that it was «one of the first blues-rock

albums», which is supposed to boil up our admiration and at the same time to

forgive the record its rawness, unevenness, and harmonica-heaviness. But the

true expression should be «one of the first white American blues-rock albums»

— British invaders like The Yardbirds and The Animals, let alone lesser heroes

like Alexis Korner, had already been doing this thing for at least a couple of

years; and in basic terms of instrumentation, there's really no reason why one

couldn't apply the term «blues-rock» to the Chicago sound — I mean, Howlin'

Wolf's recordings from the late Fifties / early Sixties certainly «rock» just

as hard, if not harder, than these ones. A thinner drum sound, perhaps, but

that's about it.

Still, there are enough historical and other

reasons to at least be happy that the tapes were not completely lost, and that

it is possible to trace Butterfield's story way back into late 1964. And, heck,

when they really speed up the tempo and Paul is blowing away and the rhythm

section is rolling and grooving, like on ʽPiney Brown Bluesʼ, for instance, it

takes a mighty (anti-)intellectual leap to not get caught up in the excitement

— at least a little bit.