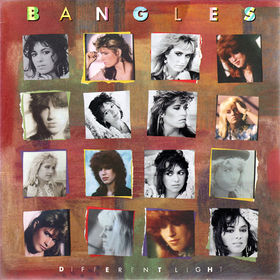

BANGLES: DIFFERENT LIGHT (1986)

1) Manic Monday; 2) In A

Different Light; 3) Walking Down Your Street; 4) Walk Like An Egyptian; 5)

Standing In The Hallway; 6) Return Post; 7) If She Knew What She Wants; 8) Let

It Go; 9) September Gurls; 10) Angels Don't Fall In Love; 11) Following; 12)

Not Like You.

Almost everybody who cares about the Bangles

more than about the history of MTV usually speaks of Different Light as a serious step down in overall quality for the

band. However, this is «symbolically» true rather than «truly» true. The

moderate success of All Over The Place

had opened the doors to fame and fortune, and the girls were definitely not

above trying it out — they agreed to tour with Cyndi Lauper and eventually

attracted the attention of Prince himself, never the one to nonchalantly skip

over such a «tasty treat». And this encounter pretty much sealed their fate:

once you start taking orders (or even recommendations) from Prince, there is no

turning back — besides, considering how niftily Prince managed to remain his

own master while at the same time drawing in the big bucks, taking advice from

the guy naturally seemed like a big win.

So we have ʽManic Mondayʼ, written by The

Artist specifically for the Bangles and released as the first single from their

second LP. Is it a good pop song? You bet it is. The little baroque keyboard

riff that functions as the main melodic hook is unforgettable, as is the vocal

melody of the chorus (and if you think that "it's just another manic

Monday, I wish it was Sunday, 'cause that's my fun day" is a lame lyric,

you probably come from way before the era of Rebecca Black). Is it «an

important, progressive development» in the history of Bangles sound? No, it

isn't, since it shifts the emphasis away from the poppy, but bite-y electric

guitars and the sarcastically intelligent atmosphere of that sound — and moves

into the kind of territory inhabited by... not even so much by Prince as by

Madonna: the "all of my nights..." midsection could very easily be

pictured sitting somewhere in the middle of True Blue. Moreover, Susanna Hoffs does her best to sex up her

vocals, developing a «bedroom voice» that does sound suspiciously close to

Madonna's.

Most albums are usually judged on the strength

of their lead single — in this particular case, ʽManic Mondayʼ is not very representative of the rest of the

album. First, most of the songs are still originals, composed by Hoffs and the

Petersons, or covers of artists you'd expect

them to cover (Big Star, Jules Shear). Second, the guitars make a loud return

on the second track already, and rarely let us down afterwards — and they are

good, trusty, jangly Bangl-y guitars, not the generic pop metal crap that

ruled over mainstream rock releases in 1986. What does unite these songs with ʽManic Mondayʼ is (a) the production,

which feels slicker and more technology-dependent than before, and (b) the

overall feel — where All Over The Place

kicked ass and felt strong and self-assured, Different Light comes across as a spiritual surrender... «...in

which the ladies embrace their feminine side and purge their pretty heads of

superfluous ideas».

Not totally, of course. New bass player Michael

Steele, for instance, gets to contribute ʽFollowingʼ, a sparse acoustic ballad

(which could have been even more effective, I think, without the unnecessary

synthesizer hum in the background) that could serve as a blueprint for most of

Ani DiFranco's career: punchy jazz/folk chords, strong, independent vocals, harsh

post-breakup lyrics etc. It is not as immediately overwhelming as the big pop

hits, but in time, it gets its warranted status of overlooked highlight.

But on the other side of the deal, you have

ʽWalk Like An Egyptianʼ — written by Liam Sternberg, the song is musically

innovative (it sounds like a light calypso number turned into a speedy rock

anthem at the last moment) and lyrically fun, yet ultimately quite light-headed

and trifling: naturally, it ended up becoming one of their largest hit singles,

if not the trademark song to be

remembered by (particularly since everyone except for Debbi trades lead vocals

across the different verses). Great stuff for parties, but if you ain't much

of a party goer, chances are you will get tired of these friendly hooks fairly

quickly.

Nevertheless, far be it from me to call Different Light a «bad» album —

«disappointing», yes, but if all «disappointing» albums had this kind of quality,

we would have to rethink the meaning of the word itself. Frankly speaking,

there are no bad songs here. The Jules Shear cover is irresistible, even if

the main guitar riff is made to sound like ABBA and Hoffs' vocals are once

again done Madonna-style. The interpretation of Big Star's ʽSeptember Gurlsʼ, once

again with Steele on vocals, is respectful and well executed (and was quite

instrumental, by the way, in restoring Big Star's reputation and earning the

struggling Alex Chilton quite a bit in royalties). ʽStanding In The Hallwayʼ,

ʽReturn Postʼ, ʽNot Like Youʼ — all of them catchy, fun, enjoyable numbers. Calling

them «slick» is probably justified, but if we only get to remember what was really slick in 1986, one of the worst

years in mainstream pop music history, Different

Light will have no choice but to, well, be seen in a different light.

In other words, the album is nowhere near close to a catastrophe on its own — it sets

the girls up for a fall, indicating the inevitably downwards direction their

career would take from that point, but the LP itself is well above any

devastating criticism, and still a must-have for all lovers of good pop music,

though probably not for the average

«girl power» fan. Isn't it ironic, really, that Prince was so impressed by one

of the girls' punkiest songs (ʽHero Takes A Fallʼ), that it stimulated him to

write them one of their «girliest» songs — one that they accepted and swallowed

up without a hitch? Isn't that much

better proof of the man's Mephistophelian powers than whatever Tipper Gore ever

spotted in his silly sexist lyrics?.. Oh well, never mind. Sexist, feminist,

slutty, or punkish, or both, this is a certified thumbs up in any case.

Check "Different Light" (MP3) on Amazon